There is this undeniable moment when you witness something unfair. It strikes you in the gut before your mind can catch up. A child gets blamed for something they didn’t do, a colleague takes credit for your work, or a person in power bends the rules to their advantage while expecting you to comply. And we’re all familiar with this unmistakable feeling: this is not fair.

And still, time and time again, we swallow the truth, dilute it with justifications, and look away while someone else bears the weight of it.

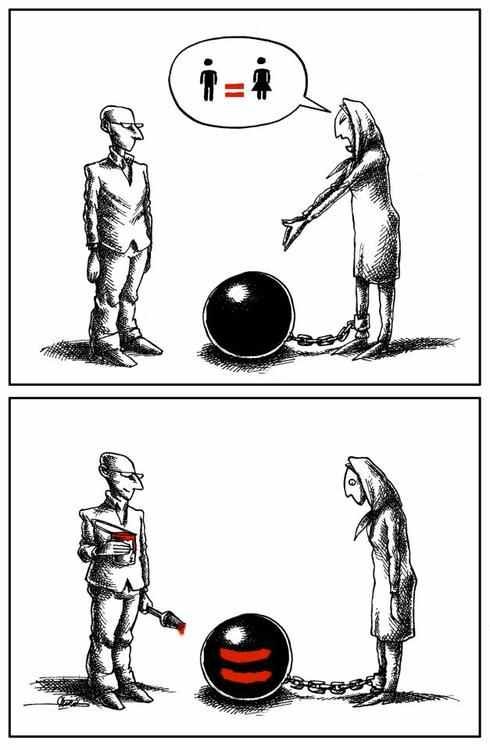

“A dominance hierarchy is a social structure where some people are allowed to hit you, and you’re not allowed to hit back. It is defined by a sustained, institutionalised asymmetry of aggressive-submissive interactions.”

— an excerpt from Arnold Schroder’s episode “How to Tell If Someone Is Hitting You”

From the earliest civilisations, power has been wielded to maintain control over those deemed ‘weaker’. Monarchs ruled with divine authority, feudal lords extracted labour from peasants, and industrial magnates exploited workers in factories. Each era has had its own version of dominance, reinforced by societal norms, religious doctrines, and political systems that kept the powerful in control. But history also tells us that no hierarchy is ever absolute.

The Capuchin Monkey Experiment: Even Animals Know

In one of the most well-known social experiments, primatologist Frans de Waal and his team demonstrated that Capuchin monkeys inherently understand fairness. In the study, two monkeys were placed side by side and given a task to complete in exchange for food. One monkey was given a slice of cucumber as a reward — something it was happy to accept. But the moment the other monkey receive a grape (a far superior reward for the same task), the first monkey lost its mind. It banged on the walls, threw the cucumber away in protest, and refused to continue.

This is pretty profound. Fairness is not just a human construct. It’s biologically hardwired into us meaning that it’s not something we have to learn, it’s something we already feel in our bones.

So, why do so many of us accept unfair treatment in our lives?

The Psychology of Submission and the Cost of Early Conditioning

The issue here isn’t that people don’t recognise injustice. The issue is that we have been trained to tolerate it — sometimes so deeply that we mistake endurance for virtue.

If you grew up in an environment where authority figures were unreasonable, you learned early that pushing back had consequences. Maybe you had a parent who dismissed your feelings, an older sibling who made the rules, or a teacher who played favourites. Slowly, you were conditioned to accept that some people just get away with things, and questioning it would only bring trouble. I know of many cultural traditions that reinforce this conditioning, with one of the most rigid being Confucianism’s emphasis on filial piety. The doctrine teaches blind obedience to parents, demanding ‘dutifulness’ regardless of their actions or character.

While respect for elders can be valuable, the expectation that children must never question or challenge their parents, even in the face of mistreatment, has long been used to justify emotional and psychological control. It assumes parents are always wise and just, when in reality, they are as flawed as anyone else. Worse, it conditions entire generations to prioritise obedience over integrity, leading to many of us to internalise the idea that power must be endured rather than questioned.

By the time we become adults, we have internalised this imbalance that we barely notice it happening. We tell ourselves that it’s just how the world works. Instead, we rationalise bad behaviours: Maybe they didn’t mean it that way. Maybe I’m overreacting. Maybe I deserved it.

No. You didn’t deserve it. And no, you’re not overreacting. The first step in dealing with unreasonability in our lives is unlearning the instinct to excuse it.

The Historical and Philosophical Roots of Power and Unreasonability

Throughout history, those in power have maintained control not through fairness, but through narratives that justify their dominance. From divine rights of kings to modern corporate hierarchies, every oppressive system has relied on a core belief that some people deserve more than others.

Philosophers have long debated the nature of justice. Plato’s Republic explores the idea that justice is simply what benefits the strong. Machiavelli, in The Prince, argued that rulers must often act immorally to maintain power. Even Confucianism, which emphasises harmony, suggests that strict hierarchies should be preserved to maintain social order.

But history also shows us that when people push back, the narrative shifts. The fall of monarchies, the rise of democracies, and the victories of civil rights movements all began with individuals refusing to accept the dominant story. The biggest mistake we make today is thinking that injustice belongs to the past. The truth is, unreasonability is alive and well, it’s just wrapped in different language.

The Social Narrative Shifts Depending on the Victim’s Reaction

Here’s the crux of my argument: Most people who commit unfair or unjust acts know exactly what they are doing. But they will never admit it unless the person they are wronging holds their ground with absolute conviction.

This is why how you react changes everything.

Have you ever seen someone get blatantly disrespected, but because they brushed it off or laughed awkwardly, the room moved on like nothing happened? On the flip side, when someone stands their ground, when they say, No, I see exactly what you are doing, and I won’t allow it — suddenly, the social dynamics shift. The wrongdoer is forced into a position where they must either double down or retreat.

“The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don’t have any.”

— Alice Walker, an American novelist, poet and activist

This is why it’s so crucial to know what you know and act accordingly. People take their cues from the victim. If you don’t take your own injustice seriously, why should anyone else?

The NBA Experiment: Everyone Knows When Something’s Unfair

A study titled The Ball Don’t Lie: How Inequity Aversion Can Undermine Performance examined how perceived unfairness affects NBA players’ free-throw performance. The researchers found that when players were awarded free throws due to questionable referee decisions — calls that were widely seen as unfair — their shooting accuracy dropped. Even elite athletes, trained to block distractions, were psychologically affected by the perception that the opportunity was undeserved. Their subconscious awareness of injustice disrupted their performance.

This tells us that injustice is felt before it is intellectually understood, and that oftentimes, people are averse to inequality even when it works to their own advantage. The same applies to social interactions. When someone treats you unfairly, you know. They know. Everyone watching knows. Now the question is: What will you do about it?

How to Deal with Unreasonable People in Positions of (Social) Power

Dealing with unreasonable people, especially those in positions of power, does not always mean confronting them head-on. In fact, sometimes direct confrontation only invites further retaliation. I’ve put together this list with a deliberate focus on strategies that allow you to navigate these situations without escalating them. The goal is not to fight every battle, but to retain your dignity, protect your well-being, and where possible, shift the dynamics in your favour.

Recognise the Power Dynamics at Play — One of the most crucial realisations in life is understanding that power imbalances exist everywhere. You will see it in workplaces, families, social settings and institutions. Some people abuse their power simply because they can, while others do it to maintain control. If you’ve ever felt frustrated in a conversation but couldn’t pinpoint why, or if you’ve walked away from an interaction feeling small and unsure of yourself, chances are you’ve encountered a power imbalance. Instead of reacting emotionally, step back and analyse the structure of the situation. Who has influence? Who benefits from compliance? Who is silently resisting? Because power is often invisible to those who don’t have it, many people don’t realise they are operating within a system that subtly undermines them. The more unaware you are, the easier it is for others to use these dynamics to their advantage; whether it’s a family member who emotionally manipulates you, or a friend/partner who always expects more than they give.

Leverage Subtle Resistance — in my experience, subtle resistance can often be more effective than outright confrontation. When you challenge an unreasonable person openly, they may double down, retaliate, or work harder to reinforce their control over you. But when you resist subtly, you introduce friction into their dominance without giving them an obvious excuse to strike back. It could be withholding the emotional reactions they seek, refusing to give them the satisfaction of seeing you flustered or distressed. It could be responding with carefully chosen words that make them second-guess themselves. For example, when faced with an unreasonable demand, a simple pause before responding can shift the dynamic. Silence, when used intentionally, can make them uneasy and force them to fill in the gaps, often exposing their own insecurity or flaws. Asking “Why is it that we always do it this way?” can introduce doubt into an unreasonable narrative without direct confrontation.

Control the Narrative by Staying Calm — Unreasonable people thrive on emotional reactions. The moment you react emotionally, whether through anger, frustration or desperation, you feed into their game. They frame you as unstable, difficult, ungrateful, or irrational and suddenly the focus shifts from their unreasonable behaviour to your reaction. The most effective counter-strategy is composure. When you remain composed in the face of unfairness, you strip them of their ability to manipulate you. It forces them to work harder to maintain their dominance, and in doing so, they often expose their own instability or lack of control. Do not let unreasonable people dictate how you feel. It is one of the most powerful ways to reclaim your narrative and ensure that you remain in control of your own reality.

Waking Up to the Power Game

Now that you see power imbalances for what they are, I hope you take a moment to reflect, not just on the world at large, but on your own life. These imbalances exist in your personal relationships, in your workplace, and in the social circles you move through. The same tactics of control, suppression, and manipulation that shape global events also influence the dynamics in your everyday life. And once you start seeing them, you won’t be able to unsee them.

Resisting unfairness doesn’t always boil down to picking fights or raging against every injustice. Sometimes, the smartest move is recognising the setup, keeping your cool, and deciding whether to challenge it, outlast it, or remove yourself from it entirely.

The sad truth is, we are living in a time where those who thrive on deception are running the show. The narratives we consume, whether from the media, institutions, or those who seek control over us, are often curated to maintain power imbalances. Seeing through the illusion is already an act of resistance.

Start with your own life. Who holds undue influence over you? Who subtly steers your decisions, emotions, and self-worth? Pay attention to the patterns. Because once you recognise one manipulation, you’ll start recognising them all.

And when enough people wake up to that reality, the game changes. It is no longer about questioning whether injustice exists, but whether we have the courage to stop participating in it.

In a world controlled by psychopaths bullies, we feel this strike in the gut constantly. Time to stand up for a fairer world. Thank you for your clever insights and words Chusana.

To tie this into politics, look at Jonathan Haidt's Five Moral Foundations, most importantly his chart. It shows that for liberals, Fairness and Caring is all-important, and for conservatives, less so. Conservatives, OTOH, value Authority, Loyalty and Sanctity higher than F/C, and these hold little weight with the left. Haidt's conclusion (which I disagree with) is that conservatives have broader moral grounds for their positions.