What Crisis?

The invisible structures behind our crises and the tragic phases we all go through

I think there’s no denying that we now live in an era where the world seems to teeter on the edge of perpetual crisis. The voices of modern philosophers like Slavoj Žižek become more critical than ever. As political scientist, Larry Diamond, aptly describes, we are witnessing a “democratic recession” — a decline in the number and quality of democracies around the world, as well as the degradation of democratic structures within established democracies, including the US and Britain.

This democratic backsliding, coupled with economic instability, environmental degradation, and social unrest, has created the perfect storm of uncertainty and disillusionment in many of us.

Žižek is known for his provocative insights and unique blend of psychoanalysis, Marxism, and critical theory. From the start, he has been interested in what motivates people to act the ways they do — with special interest in why people passionately identify with political ideas and causes that may not serve their own best interests. And I think his insights offer a refreshing lens through which we can understand and navigate these troubled times. His famous reference of Herman Melville’s — “I would prefer not to” serves as a thought-provoking commentary on resistance, choice, and the complexity of human agency in the face of systemic pressures.

We need to acknowledge and accept that we are born into troubled times

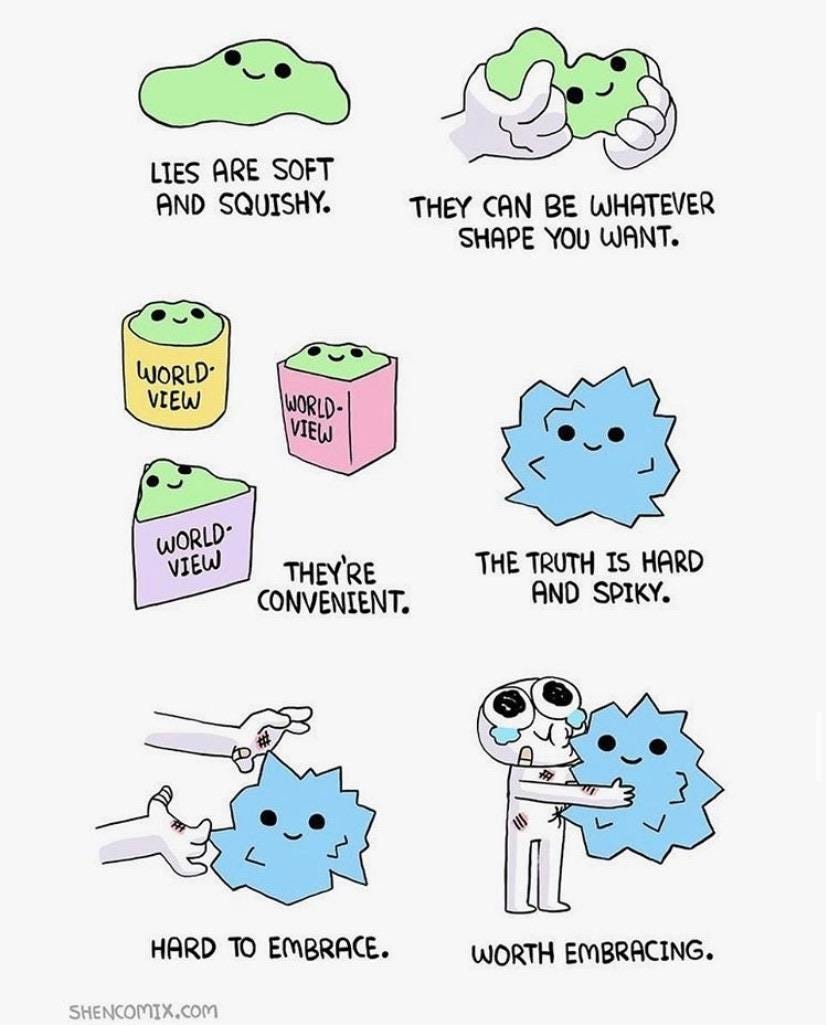

At the heart of Žižek’s philosophy is the idea that reality is inherently fragmented and that our perceptions are often mediated by ideological constructs — our existing set of beliefs that influence how we perceive the world around us (e.g. nationalism, capitalism, religious doctrines). He challenges us to look beyond these constructs and confront the uncomfortable truths of our existence. Žižek argues that the crises we face — whether political, economic, or environmental — are not anomalies but rather symptoms of deeper structural flaws within our society.

His critique extends to the notion of “post-tragic consciousness,” — a state of mind where we recognise the inherent contradictions and challenges of our world without succumbing to nihilism or despair (Read: Sarah Wilson’s piece on “Truth” and her mention of the poet, Vaclav Havel’s idea that true hope is the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of the outcome).

Referencing Daniel Schmachtenberger’s research with The Consilience Project which investigates global catastrophic risks, he outlines a three-part explanation for how individuals respond to the heightened risks arising from our hyper-connected world and technological capabilities.

Phase I: Pre-Tragic

The pre-tragic phase is characterised by a lack of awareness or denial of the gravity and interconnectedness of global crises. People in this phase may believe that current issues can be resolved with minor adjustments and technological fixes. For example, someone might think that climate change can be easily addressed by recycling more or driving a hybrid car, without recognising the deeper systemic changes needed.

Example: The world’s response to climate change 30 years ago

In the late 20th century, climate change was recognised but not perceived as an immediate threat. There was widespread optimism that technological advancements and international agreements could effectively mitigate the risks. The general belief was that environmental challenges could be managed within the framework of existing economic and political systems.

Societally, governments and corporations might promote superficial solutions or greenwashing tactics, such as single-use plastic bans, while ignoring the broader systemic issues like overconsumption and economic growth models that drive environmental degradation (Watch: Don’t Look Up spells it out for all of us to see that we, in fact, live in a society that allows those in power to bypass scientific fact and ignore the threat of our own self-destruction for the powerful’s short-term gain).

Phase II: Tragic

In the tragic phase, individuals experience a profound realisation of the severity and complexity of the crises. This often leads to feelings of despair, hopelessness, and paralysis. People become acutely aware of the catastrophic potential of climate change, biodiversity loss, and social inequality, feeling overwhelmed and powerless to effect meaningful change.

Example: The perception of humans as a “cancer” on the planet

As environmental degradation, species extinction, and climate change impacts became more evident, some people began to view humanity as a destructive force on the planet. This perspective highlights the tragic recognition that human activities are causing significant harm to the environment. The sense of despair can lead some to view humans as inherently damaging, questioning the viability of our current ways of living and governance.

At the societal level, the tragic phase manifests as widespread recognition of the metacrisis, accompanied by a sense of collective grief and fear. This can result in political and social upheaval, with movements pushing for radical change, often clashing with entrenched interests. For example, the increasing visibility of climate strikes, social justice protests, and the growing discourse around systemic racism and economic inequality reflect a society grappling with the tragic realities of our global humanitarian situation.

Phase III: Post-tragic

The post-tragic phase represents a transformation of consciousness where individuals integrate their understanding of the metacrisis with a sense of agency and responsibility. Rather than succumbing to despair, people find meaning and purpose in contributing to solutions, however small. An individual in this phase might engage in community building, support regenerative agriculture, or advocate for systemic policy changes, embracing a more holistic approach to change.

At societal level, this phase involves the emergence of new paradigms (aka perspectives) and systems that address the root causes. This includes fostering resilient communities, developing regenerative economies, and embracing global cooperation for the common good. Examples include the transition towards circular economies, the rise of social enterprises focused on sustainability, and intentional collaboration aimed at addressing climate change and social justice in an integrated manner.

Embracing Truth, Radical Hope and Acceptance

Žižek’s approach to radical hope involves a paradoxical blend of brutal honesty and unwavering optimism. This is something many of you readers are already very good at. It requires us to face the world’s darkness head-on, without flinching, and still refuse to let that darkness extinguish our inner light. This is a form of hope that I’ve been trying to practice these past few years — not blind optimism (aka toxic positivity) — but a conscious commitment to creating meaning and fostering change, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

The uncomfortable truths

Authoritarianism on the rise — leaders with authoritarian tendencies are gaining power in many countries, exploiting fears and frustrations to consolidate control, undermining judicial independence, restricting freedom of the press, and marginalising political opponents.

Member of Parliament Gábor Scheiring (right) with two colleagues all wearing signs that say ‘Enough,’ chained themselves to the Parliament building in a December 2011 protest against the increasing autocracy of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán In Hungary, Prime minister Viktor Orbán has been criticised for consolidating power and undermining democratic institutions. His government has enacted laws that weaken judicial independence, control media outlets, and restrict the activities of non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Orbán’s rhetoric often exploits fears about immigration and nationalism, appealing to public frustrations to strengthen his authoritarian grip.

In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has increasingly centralised power, particularly after a failed coup attempt in 2016. His administration has purged tens of thousands of government officials, academics, and journalists, claiming that they were linked to the coup. The judiciary has come under control of the executive branch, and media freedom has been severely restricted.

Erosion of civil liberties — across the globe, we see increasing restrictions on free speech, assembly, and other fundamental rights. Governments are using various means, from legal loopholes to outright violence, to silence dissenting voices and stifle activism.

A pedestrian detained by riot police in Hong Kong on May 27, 2020 — image credit In China, the Chinese government has intensified its crackdown on free speech, assembly, and other civil liberties, particularly in Hong Kong. The introduction of the National Security Law in 2020 has led to the arrest of numerous pro-democracy activists, the silencing of dissenting voices, and the curtailment of freedoms previously enjoyed under the “one country, two systems” framework.

In Russia, civil liberties have been increasingly restricted. The government uses legal and extralegal measures to stifle dissent, including the arrest of opposition figures like Alexei Navalny, who was poisoned, imprisoned and tragically “passed away” during his confinement in Arctic Circle prison earlier this year.

Manipulation of electoral processes — free and fair elections are a cornerstone of democracy, but we are witnessing growing manipulation of electoral processes through tactics such as gerrymandering, voter suppression, disinformation campaigns, and outright fraud, all designed to skew results in favour of those already in power

Opposition supporters protest against disputed presidential elections results at Independence Square in Mink on August 18, 2020 — image credit In Belarus, the 2020 presidential election, widely regarded as rigged, saw President Alexander Lukashenko claim a landslide victory amid accusations of widespread electoral fraud. The election prompted mass protests, which were brutally suppressed by security forces, and led to international condemnation and sanctions.

In Thailand, the 2023 general elections were similarly met with accusations of unfair practices and manipulation. Despite promises of a fair election, reports indicated significant irregularities, including vote-buying and the influence of military-aligned parties. The Election Commission faced criticism for its lack of transparency, and the results were perceived as heavily favouring the pro-military establishment, further fortifying their power and undermining democratic process.

Corruption and governance — power and corrupting nature of human behaviour often go hand in hand, undermining public trust in democratic institutions. When leaders use public office for personal gain, it erodes the legitimacy of the government and exacerbates social inequalities.

Rocío San Miguel, a prominent Venezuelan lawyer and military expert was arrested on February 9, 2024. Several members of her family also disappeared. Known for her work exposing corruption in the army — Image credit In Malaysia, the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal is one of the most notorious cases of global financial corruption. Former Prime minister Najib Razak was accused of channeling over $700 million from the state fund into his personal accounts. Najib was sentenced to 12 years’ imprisonment in 2020, but his sentence ultimately reduced by half by the Malaysian pardons board earlier this year.

In Venezuela, corruption has been rampant, especially under the leadership of President Nicolás Maduro. The country’s state-run oil company, PDVSA, has been at the centre of many corruption scandals involving billions of dollars. These funds were embezzled by government officials, contributing to the country’s severe economic crisis and humanitarian issues.

So, where’s the optimism?

This debate on how to govern a society has persisted for as long as human civilisation has existed, evolving alongside our understanding of politics, ethics and community. Francis Fukuyama, an American political scientist, argued that history should be viewed as an evolutionary process, and that “the end of history”, in this sense, means that liberal democracy is the final form of government for all nations.

For him, a liberal democratic state requires three things.

First, it is democratic, not only in the sense of allowing elections, but in the outcomes of these elections resulting in the implementation of the will of the citizenry.

Second, the state possesses sufficient strength and authority to enforce its law and administer services.

Third, the state — and its highest representatives — is itself constrained by law. Its leaders are not above the law.

“Modern history has demonstrated that a society of courageous people willing to admit ignorance and raise difficult questions is usually not just more prosperous but also more peaceful than societies in which everyone must unquestioningly accept a single answer. People afraid of losing their truth tend to be more violent than people who are used to looking at the world from several different viewpoints. Questions you cannot answer are usually far better for you than answers you cannot question.”

— Yuval Noah Harari, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century

Fukuyama argues that liberal democracy, despite its imperfections, provides the best framework for human governance due to its capacity of adaption, inclusivity, and respect for individual rights.

In the world where information flows freely, education and critical thinking become paramount. It’s essential to critically assess information and question the status quo, gaining deeper understanding of the underlying systems that perpetuate inequality — focusing on transformative changes (new perspectives or thinking systems) rather than superficial fixes (aka short term pain reliefs).

The optimism is — we already have a lot of the answers. The difficulty lies in the process of achieving them. Or as Rachel Donald has inspiringly put it in her latest post;

“It’s possible to begin with a principle: reduce the harm you cause, then help your community to reduce the harm it causes.”

Lastly, a special mention to — Audrey Tang

Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s 43-year-old former minister of digital affairs, is a staunch advocate for radical transparency in government. Her approach to governance is characterised by a blend of technological innovation and social engagement.

She has recently co-authored a new booked titled “Plurality” with Microsoft’s internal economist, Glen Weyl. The book advocates for the use of collaboration-enhancing technologies, such as blockchains, to embrace a diversity of viewpoints and foster a more inclusive society.

Tang has stepped down from her minister role in May this year to go on a world tour to speak about the theory of Plurality and educate politicians on Taiwan’s groundbreaking civic digital experiments.

What an inspiration!

Further exploration:

“The rise of authoritarianism is misunderstood – and it matters” — University of Birmingham’s Centre for Elections, Democracy, Accountability and Representation (CEDAR) provides nuanced, region-specific analyses on protecting democracy and civil liberties.

“Evolution of Trust” game — took half an hour to play but gained a whole set of wisdom on “Game Theory” explaining our epidemic of distrust and how to fix it.

The End of History: Francis Fukuyama’s controversial idea explained

“The Rule of Harm — living in a lawless world” — Substack article by Planet Critical, Rachel Donald — journalism for a world in crisis. Her writing goes deeply into the root causes of our crises.

“We are at juncture in history where we must replace hope with truth” — Substack article by Sarah Wilson . Her work is a dedication to uncovering the truth about today’s most pressing issues with clarity, empathy and a lot of relatability.

Again, a great piece touching on the most painful truths *and* the most important questions we have to ask ourselves.

At risk of greatly exceeding the scope of a simple comment, here are few thoughts:

Just as people might revert back from the “Tragic Phase” to the “Pre-Tragic Phase” through denial, cognitive dissonance and other psychological defense mechanisms, it is quite common for people to circle back from the “Post-Tragic Phase” to the “Tragic Phase” – and back to “Post-Tragic” again. For me personally, the Post-Tragic Phase is less of a steady state, and more like a temporary refuge from the “Tragic” aspects of our predicament. I find myself cycling through both phases quite regularly, and I believe it is necessary to let the emotions flow & cycle through you. Optimally, the Tragic Phase gets less severe over time, as your actions during the Post-Tragic Phase can have a permanent calming and soothing effect.

In some way, this might be like the “rock-bottom phenomenon,” where people have to let themselves be utterly devastated by grief & tragedy in order to be able to realize that there is something beyond it. Like an addict that can finally see clearer, realize mistakes, take responsibility and break old habits after hitting rock bottom, so people can look at their lives and the world with new eyes after letting despair and hopelessness destroy them.

I know from personal experience and first-hand reports from others close to me that this can have a life-altering effect similar to a brush with death, in that afterwards you ask yourself some serious existential questions, and rearrange priorities for your life. You let go of a lot of things that you thought you knew, and recognize some unquestioned beliefs as the culturally imposed misconceptions they are. You suddenly consider options that you would have never even thought about before.

Pretty much along the lines of “if I accept that my time on this planet is limited, what do I choose to do with the time that remains?” And that’s where the potential for real hope becomes tangible.

As for the whole “liberal democracy” thing: I view the entire “history-as-evolution” idea rather critically, to be honest. A bit like the Myth of Progress, or a manifestation thereof. To me it seems more like history is cyclical, and that after periods of relative stability things can revert back to something far uglier quite fast. All previous iterations of civilization had their own “Golden Age,” which they proclaimed was actually the way things were always meant to be. Fast forward a few decades, and such statements are exposed for the cosmic hubris they are.

But, again, it is important to consider that the collapse of civilization does not mean the end of the world, merely a reduction in complexity of the (mostly artificial) superstructure we’ve added to the real world. In the words of Joseph Tainter, “it may only be among those members of a society who have neither the opportunity nor the ability to produce primary food resources that the collapse of administrative hierarchies is a clear disaster.”

Again, I have the feeling that I’m just sooo far removed from what are some basic common assumptions (and from society at large). And it can be quite lonely – the image of a mountain hermit living in a cave far above the bustle of society comes to mind. To be clear: I’m not saying that I’m as wise and/or knowledgeable as a hermit, just as far removed from “normal life,” and in a position to observe and examine it from the outside. One of the ways this manifests is that I don’t believe in democracy – or at least not at this scale. As teenagers, my friends and I used to say that “democracy is when two wolves and one sheep decide what they’ll have for dinner” – the dictatorship of the majority, so to say.

Usually, the larger the group, the less coherent, the more hierarchical and complex its social organization, and the less “bright” (for lack of a better word) its individual members. As John Gowdy so aptly summarized it, “complex societies require simple individuals.”

I don’t say that there won’t be any democracy, or that the idea democracy is flawed or wrong in and of itself. I’ve just come to believe that, leaning on the ideas of Leopold Kohr (who argued that the problem is “bigness” itself) the biggest problem is that we’re thinking on scales that are simply too large to be functional. Perhaps you’re familiar with the concept of Dunbar’s number?

Most systems (apart from capitalism, perhaps) can function rather well on smaller scales – even more authoritarian modes of social organization can work well if those in authority are within reach of their subjects (and thus can be held accountable).

For me, optimism is not to be found in hopes to revert to the idealized version of the political system of the previous few decades of unprecedented material abundance, although I can understand well why this seems so comforting and thus desirable for so many people. But since the relative stability and prosperity of this system was enabled by us collectively exploiting a vast cache of fossil energy to do the “dirty work” for us, and those resources are getting more and more difficult to obtain and extract, it seems self-evident that this time is now slowly coming to an end – and liberal democracy with it.

My own form of optimism is grounded in the realization that hunter-gatherers are, on average, often just as happy and satisfied with their life as the most successful liberal democracies, or even more so. That they live decent, free, independent, meaningful and immensely fulfilling lives, within the limits of the ecosystems they inhabit, and despite occasional tragedies and hardship (or precisely *because* of said tragedies and the ability to overcome them together, as a tight-knit group of intimate friends & relatives). Yuval Noah Harari made an excellent point in his bestseller Sapiens, in the chapter “And They Lived Happily Ever After”: despite all our alleged “progress,” we haven’t gotten any happier than we used to be. Perhaps even the opposite.

What gives me reason to hope is that we humans have weathered the Ice Ages, megafauna, and countless catastrophes of various severities and scales – and yet here we are. We were immensely successful as a species, and we’ve lived decent, meaningful lives long before anyone ever thought of cultivating a field or building a city. We survived *and thrived* because we cooperated with each other, because we had a tribe/band/community to fall back on and support us, just like we supported those around us.

We did it before, and we can do it again.

(Just not all eight billion of us – aaaand, back to the Tragic Phase!)

Well I'll be damned...I'm post-tragic...nice to finally have a diagnosis. Thank you 💟