The Metacrisis, Our Fears and the Road to Authoritarianism

A reflection of our present time

The Weight of the Present

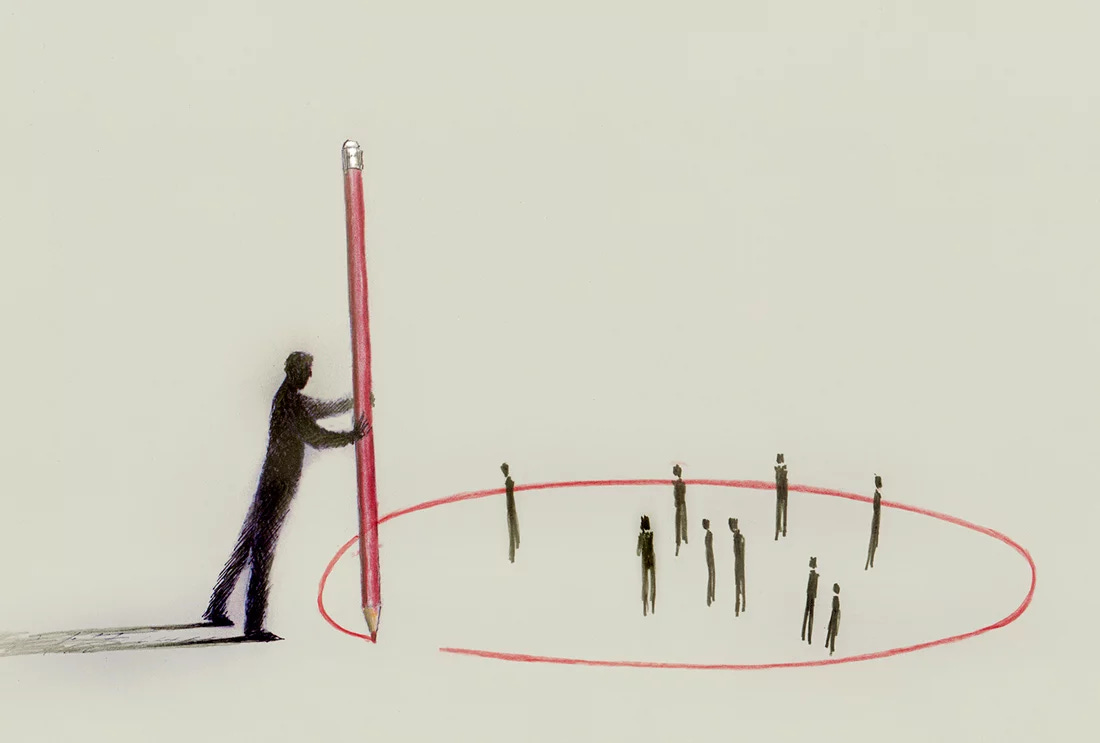

There’s a certain unease in the air. The world feels like it’s hurtling toward something, although no one can quite agree on what that something is. Beneath the endless debates, political shifts, technological advances, and global conflicts, there’s a deeper crisis — A METACRISIS — one that talks about the collapse of meaning, the degradation of truth, and the erosion of human connection.

I wrote about the metacrisis back in March last year when I first came across a conversation between Daniel Schmachtenberger (a philosopher), Iain McGilchrist (a neuroscientist) and John Vervaeke (a cognitive scientist). Their insights remain relevant today, as we continue to see the breakdown of cognitive coherence, the manipulation of human perception, and the impact of unchecked technological forces. Schmachtenberger warns of the metacrisis as an existential risk — where multiple crises reinforce one another, while McGilchrist highlights how the imbalance between the left and right hemispheres of the brain is reshaping society in ways that reduce our capacity for wisdom and holistic thinking.

We have been warned before. George Orwell’s Animal Farm taught us how power manipulates language and history to control the masses. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World envisioned a world numbed into submission by comfort and distraction rather than chains. Hannah Arendt, a German-American historian and philosopher, chronicled how fear, uncertainty, and division pave the road to totalitarianism back in 1950s. But, here we are, witnessing these warnings manifest in real-time, in ways that are eerily familiar and, somehow, disturbingly new.

If history is repeating itself, albeit with new actors and settings, then our role is to decide where we stand and how we respond.

The Metacrisis — The Collapse of Meaning and Trust

The metacrisis is the convergence of multiple crises, compounding and feeding off one another. Political instability, economic disparity, technological disruption, climate distress, and social fragmentation are all pieces of the same puzzle. And the overarching theme in all of this? A collapse in our ability to trust — trust in institutions, trust in knowledge, trust in one another.

One of the most crucial elements of this crisis is our attention. I have written about why narcissism is the main cause of evil and how it propels key figures into positions of influence. The more we give attention to fear, outrage, and division, the more these forces grow. Those who control the media, social networks, and political discourse understand this deeply, using our own psychological patterns against us.

“Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.”

— Simone Weil

Social media was supposed to connect us, but instead, it has become a battleground for attention. Governments were meant to protect us, yet many have exploited national emergencies to expand their control. The media, once a supposed pillar of truth, is now fractured into ideological echo chambers. Even science, long upheld as the ultimate arbiter of reality, is increasingly politicised and weaponised.

In Animal Farm, the pigs rewrite history to fit their agenda. “All animal are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” It’s a chilling reflection of our world today, where narratives can shift overnight, and those in power claim exclusive rights to define their truth.

“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

— George Orwell

The Rise of Fear and the Psychological Cost of Uncertainty

History has shown that when people feel unsafe, they seek security — sometimes, even at the cost of freedom, reason, or morality. Arendt’s analysis of authoritarianism reveals that totalitarian regimes do not seize power by brute force alone. They rise because fear makes people complicit. Fear makes people willing to surrender their agency in exchange for protection (Read: my piece on why good people do evil things).

“You can sway a thousand men by appealing to their prejudices quicker than you can convince one man by logic.”

— Robert A. Heinlein

We are witnessing this dynamic unfold on a global scale. Fear of economic collapse. Fear of war. Fear of pandemics. Fear of the “other”. Fear of speaking one’s mind. When fear dominates our worldview, we become easy to manipulate. We crave simple solutions. We become susceptible to propaganda that tells us who to blame. In Brave New World, people didn’t resist oppression because they were pacified by pleasure. Today, our pacifiers are different — it’s in the algorithmic feeds, performative activism, political tribalism — but it’s effective nonetheless. The ability to think critically is replaced by emotional reactionism.

Signs of An Oppressed Person

It’s essential to recognise oppression within ourselves. It’s deeply personal and it manifests in everyday thoughts, behaviours, and emotions.

Chronic self-censorship — “I better not say this, or I’ll get in trouble.” Feeling hesitant to share true thoughts in social settings, fearing backlash or ostracisation.

Emotional numbness — “I don’t even feel anything anymore.” Disconnecting from your own feelings, being emotionally worn down by stress, disappointment, or constant adaptation to survive.

Learned helplessness — “What’s the point? Nothing will ever change.” Feeling stuck in a cycle of powerlessness, refraining from taking action even when opportunities arise. Accepting oppression as inevitable rather than something that can be changed or resisted.

Constant anxiety and hypervigilance — “Did I say the wrong thing? Will they come after me?” Living in a state of fear, and always on edge about potential consequences for your actions and words.

Loss of critical thinking — “I don’t know what’s true anymore, so I just go with the flow.” Surrendering independent thought in favour of the dominant narrative, avoiding confrontation with complexity.

Avoidance of difficult conversations — “It’s not worth the argument.” Preferring silence over conflict, disengaging from discussions that challenge your views and values.

Dependence on external validation — “I hope people like me.” Having your self-worth be dictated by social approval, making you more vulnerable to manipulation and groupthink. Struggling to break free from societal norms to question the dominant ideologies that currently shape your identity and the choices you make.

Resentment towards those who challenge authority — “Why can’t they just comply?” Internalising oppression and viewing dissenters as troublemakers rather than as critical thinkers.

The times we live in are not easy. But they are not hopeless, either. If history has taught us anything, it’s that cycles of oppression are not unbreakable.

Standing up doesn’t always come in the form of grand gestures or loud public protests. It starts with the small, everyday decisions, like, how we view other people, how we treat those who we see as different to us, how we treat those we disagree with, or how we engage with truth and complexity. When families argue over politics, when friendships fracture over ideological differences, we have to remember that the real fight is to remain a compassionate human in the face of division.

“The surest way to work up a crusade in favour of some good cause is to promise people they will have a chance of maltreating someone.”

— Aldous Huxley

Staying Human in the Face of Chaos

Practice critical thinking daily — start by questioning the sources of your information. Who benefits from this narrative? Verify facts using multiple, credible sources before accepting them. Avoid knee-jerk emotional reactions by pausing before responding. Ask yourself, is this designed to provoke me? Develop a habit of asking why and how instead of just what. Read opposing viewpoints, not to agree, but to understand the underlying logic behind different perspectives.

Master the art of meaningful conversations — conversation is both a tool for connection and a battleground for division. Being a great conversationalist requires a blend of deep/active listening and thoughtful engagement. Approach discussions with curiosity rather than the need to be right. Ask open-ended questions, what experiences led you to that perspective? or how do you interpret this situation? Meaningful conversation involves knowing when to step away. Not every debate needs to be won, and not every person is ready for a nuanced discussion. Prioritise discussions that foster understanding rather than those driven by ego or conflict. Set an example by creating a space where people feel safe to express their thoughts without fear of ridicule.

Guard your attention — the modern information landscape is designed to hijack our focus and emotions. Be mindful of interactions that consume more mental space than they deserve. Choose where to invest your attention wisely, both online and in your personal life. Recognise when something you’ve read online or someone you’re talking to is manipulating your emotions, and take intentional breaks to reset the boundaries. After consuming certain content or engaging in certain conversations, ask do I feel energised and inspired, or do I feel drained, anxious and resentful? Just like a muscle, our brain requires proper nourishment, rest, and healthy stimulation.

Related articles:

Decoding Daniel Schmachtenberger on "The Metacrisis of the AI Era" — Insights from Iain McGilchrist, John Vervaeke, and Daniel Schmachtenberger on the antidote to modern despair

Narcissism - The Main Cause of Evil in the World — Understanding why everyone is talking about Narcissism like our lives depend on it

What Are You Really Chasing - Efficiency or Authenticity? — Byung-Chul Han's philosophy on the modern struggle between achieving more and connecting deeper

Why Good People Do Evil Things — And why we should resist the urge to conform

What Crisis? — The invisible structures behind our crises and the tragic phases we all go through

To try and not censor myself, I'd like to say that Environment might not just be one of those crises that we face. It is the context in which all other crises take place. We can do something about all other crises only if we still have the livable temperatures, if we still have water to drink and if droughts, fires, floods and heatwaves don't destroy our crops. On the drawing Environment is given equal 'weight' as all other crises, but biophysically speaking, that is not the case - it is by far the most important if we still want to exist as living beings. It is true that it happens at the same time as all other crises, but it doesn't have equal weight with them. To my mind.

And another related thought: what happens when we replace the word 'environment' with web of LIfe? Does that change things in a person's mind or heart? Is there a difference between these two phrases: "industries don't take care of environment and its resources", and "industries don't take care of the Web of LIfe of which we, humans, are a part"? And we are those industries too... we work for them and we buy what they sell. So - does it reverberate differently if we think about Web of LIfe, or the (non-descript) environment? For me it does. Anybody else?

Love this. Thank you