Have you ever caught yourself overreacting to something trivial and wondered, “Why did I just lose it over that?” Well, we’ve all been there, getting snagged in the web of our own inexplicable reactions. In my previous post, “Are We Built For Connection?”, we touched on how living under the constant hum of a capitalistic society shapes our mindsets, often leaving us feeling unfulfilled. This brings us to a term that’s making rounds these days: Emotional Resilience. But why should we care about building this resilience at all?

Let’s be frank; our minds can sometimes feel like they have a mind of their own, especially when it comes to negative thoughts. It’s an undeniable aspect of the human condition that negative thoughts often emerge more readily than positive ones. You drop your coffee, and suddenly the whole day feels doomed. It isn’t a flaw in our design, it’s an evolutionary trait (read more on “negativity bias”). Our ancestors needed to be alert to dangers, which meant prioritising negative information. Today, this trait translates into a propensity for anxiety and worry over seemingly minor issues, reflecting a disconnection between our evolutionary programming and the realities of modern life.

The Need for Emotional Resilience

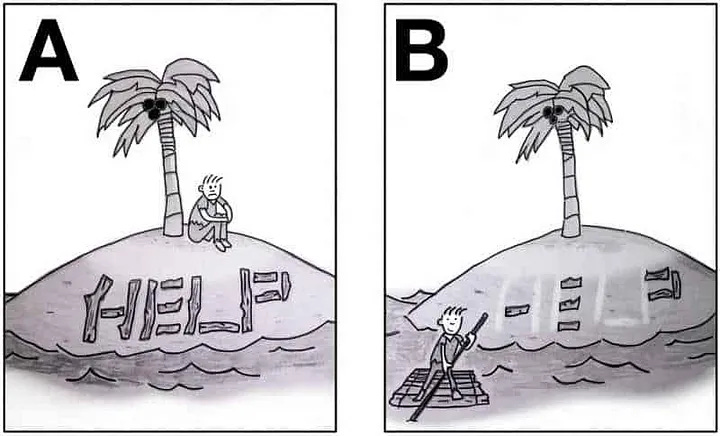

I came across this X’s thread talking about high agency individuals which perfectly encapsulated the importance of having emotional resilience and high sense of agency to effectively deal with life’s difficult challenges. Without these skills, we are at the mercy of every external circumstance that comes our way, often leading to a reactionary existence rather than one of thoughtful response.

“When you’re told that something is impossible, is that the end of the conversation, or does that start a second dialogue in your mind?” — Eric Weinstein shared how to get around whoever it is that’s just told you that you can’t do something

Ringing Bells and Drooling Dogs

Ivan Pavlov’s landmark experiment with dogs uncovered the principles of classical conditioning, a fundamental type of learning that evokes the automatic responses. By pairing the sound of a bell with the presentation of food, Pavlov found that dogs began to salivate in anticipation of food as soon as they heard the bell, even when no food was presented. It demonstrated that animals could learn to associate a neutral stimulus (the bell) with a significant one (the food), leading to a conditioned response (the salivation).

Our brains have been conditioned to react in certain ways, to certain things, and half of the time, we don’t even realise we’re drooling over our metaphorical bells. Much of our emotional reactivity is not a conscious choice but a conditioned response. The theory of classical conditioning has significantly contributed to explaining how traumas are formed and maintained in humans by uncovering the process through which seemingly neutral stimuli can become triggers for traumatic responses (Read: “The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma” by Bessel van der Kolk for a comprehensive guide to understanding trauma and its aftermath).

So, what’s your bell?

Unlike Pavlov’s dogs, humans have the capacity for self-awareness and change. As I touched on this topic in my earlier post (“The Illusion of (self) Control”), we need to accept the reality that most of us live in an environment that often prioritises external validation over genuine self-reflection.

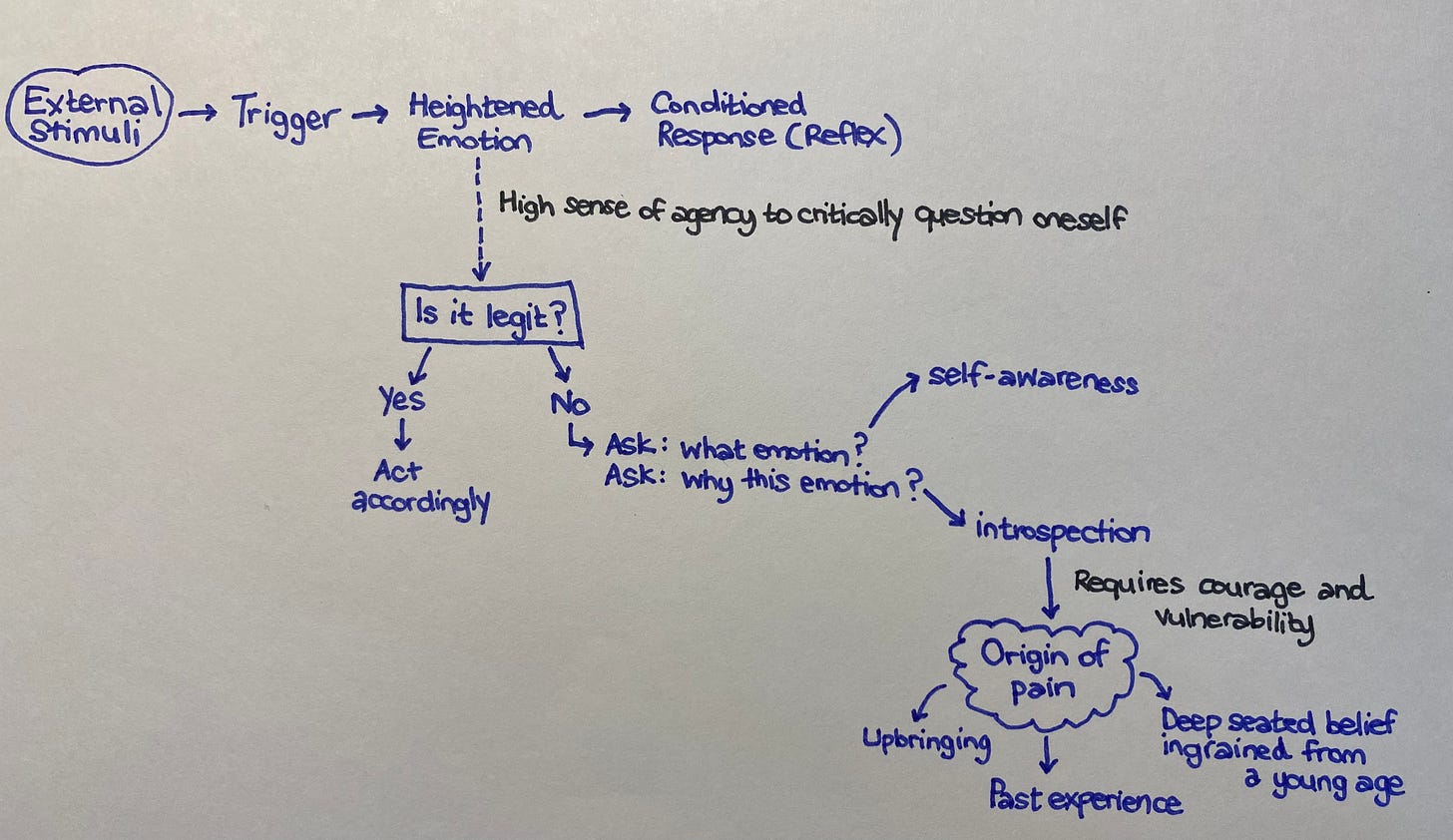

Recognising that our emotional reactions can be conditioned responses is the first step toward understanding the complexity of our behaviours.

Everyday, we encounter situations that evoke an emotional response. Sometimes, these reactions are disproportionate to the trigger, hinting at a deeper, conditioned response. For instance, a phone call with a parent that includes unsolicited advice or criticism can resurrect deep-seated feelings of inadequacy. These feelings might later manifest as impatience or over-sensitivity to feedback from colleagues, seeing it as criticism rather than constructive. Or, a night of poor sleep, especially due to worrying about an upcoming project or personal issue, can significantly lower your emotional threshold. The next day, a minor mistake made by a co-worker or partner could trigger an uncharacteristically strong response of annoyance or anger.

Some common triggers that every one of us can relate to, and autonomous emotional response associated;

Rejection → feelings of insecurity, sadness, anger

Criticism → feelings of inadequacy, defensiveness, self-doubt

Loss → profound grief, depression, existential questioning

Stress → anxiety, irritability, burnout

Traumatic memories (e.g. smell, sound or sight) → intense emotional responses such as panic attacks or flashbacks

Feeling out of control → anxiety, frustration, anger

Social isolation → sadness, depression, abandonment

Failure → feelings of worthlessness, disappointment, discouragement

Conflict → stress, anger, avoidant behaviours

Overwhelm → anxiety, panic, feeling of being trapped

Comparisons → feelings of inadequacy, jealousy, low self-esteem

Embrace “All the Feels”

I think Pixar has gotten it SO right with Inside Out when it comes to an innovative portrayal of emotions and the human mind. Taken over 6 years to develop and produce, Peter Docter and his team consulted extensively with psychologists and neuroscientists to ensure the film’s underpinnings were grounded in scientific research.

What started as Docter’s curiosity and observation in the changes in his daughter’s emotions as she grew older, turned into a masterfully-crafted illustration of the complexity of emotions and the vital role they play in shaping our experiences, reminding us that all emotions, even sadness, are essential to our well-being.

It challenges the common misconception that happiness is the only desirable emotional state (toxic positivity - Read: “Bright-sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America" by Barbara Ehrenreich explores the dark side of America's obsession with positive thinking) and that sadness must be avoided or quickly overcome.

So navigate the full spectrum of our responses, embrace the full range of our emotions. There are no ‘wrong’ feelings, only honest reactions to our world.

The journey into self awareness and emotional regulation doesn’t aim to eliminate our conditioned responses but rather focuses on developing the ability to respond to life’s challenges with conscious intent. Like any muscle in our body, the brain requires regular exercise to enhance its capacity for mindfulness and emotional control. Techniques such as mindfulness meditation, reflective journaling, engaging in therapy, and simply taking a moment to pause before reacting, are valuable tools in strengthening this mental ‘muscle’.

“Emotions are like passing storms, you have to remind yourself that you are the sky, not the weather.”

Special mention to for the inspiration behind this post when he made both of us ponder the perception of reality and how it’s so easily skewed by moods and internal stories.

I love the flowchart of trigger response! One caveat I've been working on is how not to get stuck for too long in the "introspection" step. Sometimes thinking about the problem even more doesn't help and only fuels frustration... and I get better results by letting it go and going for a run 💫. Maybe that's a way of letting the subconscious mind work on the problem, instead of the thinking self. Thank you for the post and the callout :).

That bell map is so cool. Personally, it has taken awhile to get to that place of inquiry rather than reaction from conditioning. I'd often react and then mull over it afterwards. These days I am able to catch it before I go into automode reaction. Great post!